Tactical asset allocation, by its nature, generates more transactions than buy & hold. Investors trading in taxable accounts would be justifiably concerned that the negative tax consequences of that might outweigh the benefits of TAA by shifting returns to less advantageous short-term capital gains. Our newest member feature responds to those concerns.

We track more than 40 TAA strategies in near real-time, sourced from books, academic papers and other publications. We’ve just added a new report to our members area showing the portion of each strategy’s historical returns that can be attributed to broad tax categories: short/long-term cap gains, dividends and interest.

Members click to see your new report now.

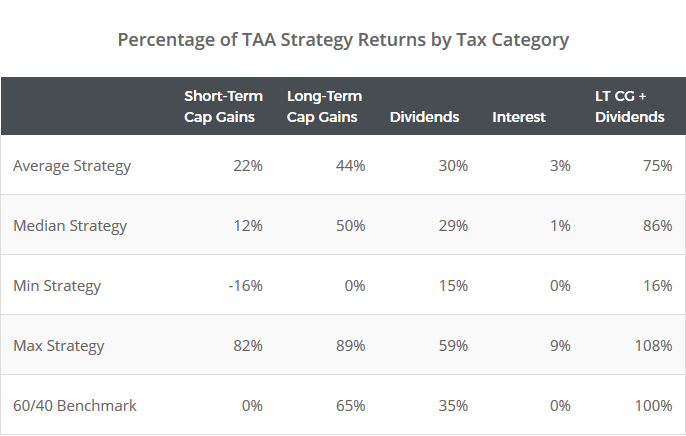

There are significant differences in this tax “profile” across the strategies that we track. We’re not going to show results per strategy in this post (for that you’ll need to become a member), but with such a large pool of strategies to consider, we’re able to draw some broad conclusions about TAA as a whole. Below we’ve shown the average and median historical tax profile of all of the strategies that we track, along with minimum and maximum values for context.

TAA has been relatively tax efficient. For the median strategy, 86% of gains have been attributed to either long-term cap gains or dividends. While many of the strategies that we track make a lot of short-term trades, most gains have come from long-term trades. That’s an important distinction. How long a strategy tends to hold positions is different than how long it tends to hold winning positions.

That makes sense when you consider that most of the strategies that we track employ some form of momentum and/or trend-following. Trades that end quickly are often losers. The strategy takes a position in an asset showing strength, it turns weak, and the strategy exits. Trades that continue for a long period of time tend to be winners. The strategy takes a position and the asset continues showing strength. Even when the asset eventually turns weak, the strategy has already profited enough that the trade is a net gain.

In short, concerns that TAA as a whole shifts the majority returns into short-term cap gains are invalid. The numbers just don’t bear that out. Having said that, there are individual TAA strategies that are not remotely tax efficient. You see that in the min/max stats and in the skew in the average vs median stats. We’re not accountants and this is not tax advice, but we think it’s safe to say that some strategies are more appropriate for taxable accounts, and others are more appropriate for tax-deferred/exempt accounts.

Tax efficient TAA:

Unfortunately, the following will only make sense to members with access to this data on a per strategy level.

There is (obviously) some relationship between how often a strategy trades and the percentage of returns derived from short-term gains. Strategies that trade less often (ex. Stoken’s ACA) or in smaller size (ex. US Equal Risk Contribution) will tend to incur less short-term gains. There are some fairly active strategies however that break this mold. Notice for example, Alpha Architect’s Robust Asset Allocation and Meb Faber’s GTAA 5 and 13.

These strategies are all designed in a way that tends to make them more efficient. First, they allocate a fixed portion of the portfolio to a given asset, and when that asset is out of favor, they leave that portion of the portfolio in cash. Positions are not constantly sizing up or down based on what other assets in the portfolio are doing. Second, they don’t employ cross-sectional (aka “relative”) momentum. That means that they’re not switching from one asset to another that is only marginally better. That reduces the number of short-term trades made for minor reasons. That’s likely to hurt pre-tax returns, but may result in superior after-tax returns for investors trading in a taxable account. More on this concept in an upcoming blog post.

One last note:

Even if all gains are of the long-term variety, closing out profitable trades is inherently less tax efficient than continuing to hold them, all else being equal.

Consider two hypothetical traders trading in taxable accounts. The first holds SPY (S&P 500) for 30 years, and then sells his position. The second initiates and closes a position in SPY every 2 years for a total of 30 years. We’re ignoring wash sales and transaction costs for simplicity’s sake, and we’re assuming that each trader paid his tax bill from his trading profits.

Taxes aside, both traders enjoy the same return. But after accounting for taxes, our first trader outperforms. That’s because our second trader is giving up a portion of the portfolio every two years in taxes, so he doesn’t enjoy the same degree of compounding.

Why are we ever willing to trade in taxable accounts then? Because we believe that the performance benefits of TAA, both in terms of generating returns and managing losses, outweighs that drag on returns. In the real-world, investors don’t hold assets for 30 years, and without fail, they buy and sell assets at precisely the wrong moment out of greed and fear. Having a thoroughly researched, mechanical trading strategy able to maximize gains and manage losses ensures that investors make smart decisions, even if that sometimes requires triggering taxable events.

We invite you to become a member for about a $1 a day, or take our platform for a test drive with a free limited membership. Put the industry’s best tactical asset allocation strategies to the test, combine them into your own custom portfolio, and then track them in near real-time. Have questions? Learn more about what we do, check out our FAQs or contact us.

Calculation notes:

- All positions are assumed to be closed and moved to cash on the final day of the test in order to capture any unrealized capital gains.

- The definition of short versus long-term capital gains is based on US tax laws as they stand today.

- The interest calculated here is from a strategy’s use of a “cash” asset. Depending on the actual asset traded, these gains may actually count as more tax-advantageous dividends.

- We’ve simplified these results to a large degree, and there’s some nuance that we haven’t taken into consideration. In some cases, that nuance could make these results worse, such as the impact of wash sales, qualified versus ordinary dividends, etc. In others, it could make these results better, such as intentionally executing a sale a bit early or late in order to qualify as a short or long-term cap loss/gain.

- These results are based on dollar gains, as opposed to percentage gains. That means that events later in the backtest, when the hypothetical portfolio size was greater, will have a larger impact on these results than events earlier in the backtest. We’ve taken this approach because it’s easier to audit for accuracy, but both approaches lead to similar results.

- There are a few strategic buy & hold strategies that we track in the members area (ex. Harry Browne’s Permanent Portfolio). We’ve included them in these results so that this blog post matched our members area stats. Had we excluded them, it wouldn’t have moved the needle by much (ex. median ST CG from 12% to 14%) and the conclusion of the post would have been the same, but in full disclosure, there are a few strategies included here that are not strictly TAA.